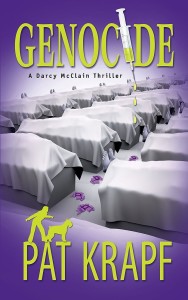

After several edits, Genocide, book three in the Darcy McClain and Bullet thriller series, is with Caroline, one of my editors, for what I hope is the last round. The book has passed through three pairs of eyes: Caroline’s, Arlene’s (my other editor), and my own. Discussing book edits brings to mind a blog post Arlene wrote in July of this year. Like Arlene, I have also experienced sleepless nights and anguish worrying about potential mistakes in my books, and like many authors, I have done my best to avoid errors. A brief excerpt from Arlene’s article follows:

When editors make mistakes . . .

Editors make mistakes? What? How dare I go on record to state such a thing! Right off, let’s get one thing clear: editorial errors are inevitable. If that surprises you, it shouldn’t—we’re only human, after all (I know that’s hard to believe). While many editors are perfectionists, most of us also know perfection is impossible to achieve. Let me tell you from firsthand experience that the quest for perfection in a world where perfection doesn’t exist is an issue that causes many of us a great deal of anguish and even sleepless nights. It’s one of the hazards of the job. Can a book be error free?

Editors make mistakes? What? How dare I go on record to state such a thing! Right off, let’s get one thing clear: editorial errors are inevitable. If that surprises you, it shouldn’t—we’re only human, after all (I know that’s hard to believe). While many editors are perfectionists, most of us also know perfection is impossible to achieve. Let me tell you from firsthand experience that the quest for perfection in a world where perfection doesn’t exist is an issue that causes many of us a great deal of anguish and even sleepless nights. It’s one of the hazards of the job. Can a book be error free?

Read her entire post, “When editors make (or miss) mistakes…”

While Caroline edits Genocide, I am taking a short break from novel writing before I begin the first of many revisions to book four in my series, Clonx. It is currently in draft form. The thriller is set largely in Texas, but some chapters are set in New Mexico, where Darcy and Rio return to settle some personal matters. The scientific subject of the novel is cloning. In Clonx, Darcy is in Texas for Vicky’s wedding. While on her daily run, Bullet discovers a trash bag submerged in a creek. Inside are the pulverized remains of renowned geneticist Dr. Catherine “Cate” Lord, who has been under fire from Zyclon, a bioethics advocacy group diametrically opposed to her research on human cloning. Although the evidence points to Zyclon as the prime suspect in her murder, Darcy soon discovers Cate had many enemies and any one of them had good reason to kill her.

To kick off my writing series, I’ll answer questions I’ve received from readers. Some have already been addressed in past blog posts, which I will link to, but I am happy to respond again and/or give more detailed answers as some readers have requested. Five questions I have repeatedly been asked are general in nature, so let’s start there.

Are you related to Patrick Krapf? Have you seen him on YouTube? Why do you have such loud music on your website?

Three different questions from three different readers, but all associated in one way. No, I am not related to Patrick Krapf that I know of. And if you hear loud music or don’t like the videos on my website, as some blog subscribers have mentioned, you are on the wrong website. I’ve never had music or videos on my site, but I do plan to add book trailers in the near future, so please watch for them.

Is the p in your last name silent?

Is the p in your last name silent?

Speak to Americans and most will tell you yes. But when I asked several German friends, they responded unanimously—no. “You definitely do pronounce the p and the f in Krapf as “pfhh.” If your last name was Kraph, then the p would be silent and it would be pronounced as an f.” There you have it, straight from several Germans. And if you can master the “pfhh,” you have my admiration. I have not succeeded in doing so without spitting on anyone, so I have since refrained and fallen back on the silent p. On an interesting note, after considering this reader’s question and conducting some research on the surname, I discovered the name, which has many variations in spelling, was first recorded in South Holland around Rotterdam before appearing in the Bavarian region of Germany. And citing genealogical websites, the first Krapf migrated to the US in 1748 and settled in Pennsylvania where most Krapfs still reside today. An equal number live in the state of New York.

When you are not writing, what are your favorite ways to relax?

Spending time with Kai, my giant schnauzer, gardening, photography, cooking, and traveling.

What inspired you to write?

A promise I made to myself. At age eight my reading skills sucked, and my third-grade teacher informed my parents I would never get into college unless I improved. So every weekday night while everyone else watched television, I sat in my bedroom with my mother and together we plowed through the Nancy Drew, then the Hardy Boys series. It was a slow start, but five months later you couldn’t pry a book from my hands. I was addicted to reading and told my mother, “I’m going to write a book one of these days.” Granted, it was many years before I fulfilled that dream, but I released the first book in the series, Brainwash, in April 2014, and the second, Gadgets, in 2015. Both are available in print and e-book on Amazon .

Was Brainwash your first novel?

No, my first novel was Blind Revenge, a standalone. Later, I will incorporate it into the Darcy McClain series and retitle it.

I’ve seen your title Brainwash as one word and two words. Which is correct?

In terms of the book, either one. The word “brainwash” is one word and the title was intended to be one word, but my cover designer, Fiona Raven, made it two so it would stand out. This allowed us to make the type bigger and bolder, especially “WASH,” which is a shaded yellow in color.

How do you come up with titles?

I focus on short titles—quick recognition and easy memorization—and ones that sum up the essence of the entire book, if possible. For example, Brainwash was the name of the artificial intelligence/nanotechnology program being carried out by Los Alamos National Laboratories. The program was the scientific plot for the novel. In Gadgets, Paco was a gadget geek who loved to own the latest in new technology and had the expertise and knowledge to build his own weapons. A Genocide is the mass murder of a group of people, and this thriller is based on plot to exterminate all gays and lesbians. Someone recently asked me if all of my book titles would begin with B or G. No, that the first four novels I have written do, is a fluke. And as I stated above, Blind Revenge will be retitled when it is released.

How do you find time to write?

I make time. And it helps that writing is an addiction. Often it controls me. I also credit my ingrained self-discipline—a learned trait from my high school days when I was enrolled in correspondence courses from the University of Nebraska Extension Division. I worked to a strict schedule then, and I do today. I set goals, prioritize them, and assign deadlines. This routine works well for me.

Do you get writer’s block?

I’ve suffered from writer’s block on three occasions. First, as a young writer with little life experience, and therefore little to say. However, I did write poetry occasionally, a few short stories, and I kept a diary throughout my adolescence. My second bout was when I decided to write my first book, Blind Revenge. I began by writing romance, or attempted to. I like romance, but it simply wasn’t the genre for me, and I came to this conclusion when, four weeks later, I was still staring at the same six-paragraph page. The last time I experienced writer’s block was in 2013 after my web designer Lindsay said, “You really should blog on your website.” My first thought: Blog about what? My second thought: Blogging is time-consuming. A week later, I came across an article titled “The Problem With Memoirs” by Neil Genzlinger, staff editor at The New York Times. Many years ago, I toyed with writing a memoir, but always came to the same conclusion as Mr. Genzlinger: “There was a time when you had to earn the right to draft a memoir.” I’m not interested in writing a full-blown memoir, so I’ve settled for writing a blog biography. Spending my formative years overseas was in many ways a unique experience, but the high points can be covered in a series of blogs, emphasizing what is noteworthy and glossing over the ordinary. There are people in this world who have achieved the remarkable or overcome great obstacles; for them a memoir is fitting.