Happy New Year and the best of everything in 2018—Darcy, Bullet, and Pat.

Cruising Milford Sound.

Today I’m wrapping up my Down Under blog series and want to share a few parting photos that I hope you will enjoy. As I’ve mentioned on several occasions, I am not writing a travel blog per se. I only post about locations that will appear in future Darcy and Bullet thrillers. So yes, I do plan to set a novel Down Under, and many of the countries in my current posts will be settings for forthcoming books.

Cruising the Milford Sound

a glimpse into my 2018 blog posts: in the coming months I will post about my Canadian trip and my St. Barth’s visit, also settings for new Darcy and Bullet novels. After these travel posts, I will do a series on art and architecture. Why, you might ask, would I write about these? Because both subjects are dear to Darcy’s heart and mine. Watching a talented person create a work of art, design a structure, or write a book is inspiring unto itself, and art and architecture play a part in my thriller series.

KEAS

Let’s start with those cheeky keas, heralded as the world’s most intelligent birds. Dubbed “the clown of the alps,” and the only alpine parrot in the world, the kea is native to the forested and mountainous regions of New Zealand’s South Island. The screeching cries of “keeeaa” alert you to the presence of these highly social and inquisitive birds.

Although I haven’t had the privilege, I’ve been told that if you see a kea in flight you will never forget it. The birds transform from olive green to brilliant flashes of orange, scarlet, yellow, blue, and turquoise.

Keas are hardy birds that tolerate a range of temperatures, and they thrive on everything from berries, fruits, roots, and leaves to even carrion. They also loiter around picnic sites—an easy source of junk food. Insatiably curious, charismatic, and mischievous, these natural sleuths are bold, relentless, and downright destructive, but so cute. Easy for me to say when I haven’t experienced their fondness for rubber—destroying car door seals or chewing through wiper blades. I did get a kick out of seeing several board a bus during our tramping tour.

According to a British tourist, he had his passport stolen by a kea. The passport was stored in a brightly colored bag in the luggage compartment of a bus headed for a boat tour of Milford Sound. The kea struck when the bus stopped and the driver was busy in the luggage compartment. The driver startled the kea, which flew away with the passport.

Years ago, when a kea was spotted attacking a live sheep, the birds were branded as killers and a bounty was placed on their little green heads. Tens of thousands were killed, but today they are a protected species.

But why all the signs warning people not to feed them? Besides the bounty, their love for high-fat junk food very nearly killed them off. So for their sake and ours, do not feed the keas.

MELALEUCA

In the wilderness of Tasmania’s Southwest National Park, the history of its first inhabitants, and later its mining explorers, is being preserved at Melaleuca—renowned for its world heritage area and also for its mining history. A small mining settlement was established in the region in 1930s, where high-grade alluvial cassiterite (tin oxide) was mined.

While digging deeper into the history of tin mining during my research on Sir Henry Jones, I discovered the life and accomplishments of Charles Denison “Deny” King, an Australian naturalist, ornithologist, environmentalist, painter, and the first tin miner in Melaleuca. To read more about him and the Deny King Heritage Museum, http://tasminerals.com.au/news/news/about-deny-king-and-the-deny-king-heritage-museum,-melaleuca/

I also discovered during a conversation with one of the “birdies” from our tour of Melaleuca that they were not in search of “simply a green parrot” but were on a heated search to catch a glimpse of “the critically endangered orange-bellied parrot that breeds only around Melaleuca.”

The Melaleuca was originally part of the homelands of the Needwonnee Aboriginal people, and the Needwonnee Walk shares the stories of these original custodians of the land. Photo left: On the Needwonnee Walk.

The Melaleuca was originally part of the homelands of the Needwonnee Aboriginal people, and the Needwonnee Walk shares the stories of these original custodians of the land. Photo left: On the Needwonnee Walk.

Black swans at Melaleuca

Today’s Melaleuca is still virtually untouched, with only six thousand visitors each year. Due to the remoteness of the region and limited accessibility—by foot, plane, or boat—the area has maintained its wildness. Visitors’ facilities are intentionally rugged, catering to trampers, bushwalkers, day-trippers, and bird-watchers. As I wrote in a previous post, we flew into the small airstrip and then traveled on foot and by boat to tour the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area.

Sadly, this wilderness area suffered a bad bushfire in 2016. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3429623/Tasmanian-World-Heritage-area-devastated-bushfire.html

SIR HENRY JONES

The infamous staircase at The Henry Jones Art Hotel

A last word on Sir Henry Jones. While Jones had a reputation for frugality, he was a very generous man who simply disliked spending money on “fripperies.” Rather than use first-grade timber to panel the Top Room at the Henry Jones hotel, Sir Henry preferred to reserve the high-quality wood for the crates that would be used to export his IXL jams around the world.

This grand staircase, also in the Henry Jones Hotel, has four carved newel posts, which support the handrail. Three have been decorated with stippling. When Jones walked by and saw a young lad from the factory floor working on the last post, he sent him back to work packing crates—an example of Jones’s abhorrence for needless expense.

LOVE LOCKS

From the Pont des Arts bridge in Paris to bridges in Melbourne and Sydney, love locks have been cut off footbridges, melted, recasted, and refiled. In some cases, they have become works of art with the proceeds donated to charity. From a previous post of mine: https://patkrapf.com//2015/06/18/europe-2013-the-notre-dame-bells/

My last shot of Australia as we flew back to the Unites States from Sydney.

For now, I will say a fond farewell to the land Down Under, but I will see you soon, Aotearoa—the Maori name for New Zealand, which translates as “the land of the long white cloud”—for we are already planning a repeat visit.

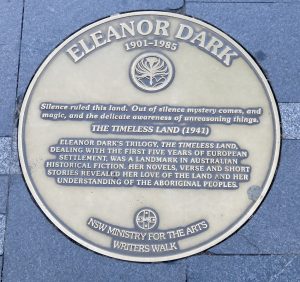

Writers Walk in Sydney.

You will notice I use famous quotes in all of my Darcy McClain and Bullet thrillers and I’ll leave you with one now from Eleanor Dark. “Silence ruled this land. Out of silence mystery comes, and magic, and the delicate awareness of unreasoning things.” The Timeless Land (1941).

While doing research on Hobart, I came across some interesting information on the Drunken Admiral, which was built in 1825–6. Considered one of the finest structures in the colony, the building was constructed of brick with a stone facade, and a slate roof imported from Scotland—quite extravagant for its time. After various uses throughout the years, from a depot for new immigrant arrivals, to a home to two brothers who ran it as a flour mill and warehouse, to housing for Henry Jones’s staff after he purchased it in 1923, it finally became a restaurant in 1979. But the most intriguing fact is that the Drunken Admiral has had its share of ghost sightings. The restaurant owner has reported glasses exploding in people’s hands, bottles sliding off shelves, and women leaving the restroom complaining of feeling as though they have been strangled. In 1880, a Chinese market man was found hanging in the courtyard behind the restaurant. In the 1960s, a worker at the Drunken Admiral who knew nothing about the hanging claimed he saw a Chinese man drift through the walls.

While doing research on Hobart, I came across some interesting information on the Drunken Admiral, which was built in 1825–6. Considered one of the finest structures in the colony, the building was constructed of brick with a stone facade, and a slate roof imported from Scotland—quite extravagant for its time. After various uses throughout the years, from a depot for new immigrant arrivals, to a home to two brothers who ran it as a flour mill and warehouse, to housing for Henry Jones’s staff after he purchased it in 1923, it finally became a restaurant in 1979. But the most intriguing fact is that the Drunken Admiral has had its share of ghost sightings. The restaurant owner has reported glasses exploding in people’s hands, bottles sliding off shelves, and women leaving the restroom complaining of feeling as though they have been strangled. In 1880, a Chinese market man was found hanging in the courtyard behind the restaurant. In the 1960s, a worker at the Drunken Admiral who knew nothing about the hanging claimed he saw a Chinese man drift through the walls.