Main Character

Darcy McClain is a former FBI agent-turned-private investigator. Although her former position with the FBI plays a minor role in my thriller series, I still researched the subject in detail. I started at the library, poring over nonfiction material. Then I conducted research on the FBI’s website. I was also fortunate to interview several agents at writers’ conferences. There is an FBI agent named Jack in Clonx, and I will definitely contact the FBI field office in Dallas to learn more about how local agents work as I flesh out Jack’s character. As for private detectives, Darcy is licensed in the state of California. Years ago, prior to writing my thriller series, I attended several courses at the Screen Actors Guild in Los Angeles, along with a friend who happened to be a retired LAPD detective. He gave me some unique insights into the daily lives of officers and detectives that work street crime. I’ve used his information as a foundation for Darcy’s experiences.

Bullet

Nothing compensates for writing about a giant schnauzer like owning one, but I do not advocate buying or adopting a giant unless you have owned one before or if you are well educated on the breed. Please do your homework prior to even considering a giant schnauzer. I’ve been asked to “include more of the dog” in my series. I intend to do just that. In Clonx, Bullet plays a major role as a scent detection dog. How will I do my nose work research? I’ll begin with online sites and books dedicated to the subject, and then I will attend nose work classes. In addition, I plan to consult with fellow giant schnauzer owners who are active in the nose work field, as well as confer with a friend whose lifework has been search and rescue. The greatest reward that comes from all of this research is knowledge, on so many subjects.

Secondary Characters

I was once asked what I disliked the most about research. I don’t like researching topics such as child abuse. It ruins my day and drags me down emotionally, but I stuck with it, doing so in small doses, until I felt I had an understanding of Paco’s hatred toward his abusers and his need for revenge. After several self-edits of Gadgets, I gave the book to a fellow writer to read. She had “some insights into child abuse,” she informed me, but never went into detail and I did not pursue the subject with her. My research and her editorial comments proved invaluable. As for Charlene, her character is based on a combination of research, personal observations, and direct interaction with teenagers.

Settings

I rely on firsthand experience. Brainwash and Gadgets are set in New Mexico because I love the state and have traveled extensively throughout the area, and we own a vacation home there. The setting for Genocide is California. I lived in the southern part of the state for over sixteen years. Clonx is set in the Dallas/Fort Worth Metroplex, where I’ve been a resident for more than twenty-five years. I plan to set several novels in certain locations abroad, places I’ve lived in or have visited on many occasions. While online research might be a good place to start when scouting out settings, nothing substitutes for walking in the footsteps of your characters. Google Maps is a great tool, but it covers only the visual. For instance, after I wrote my first draft of Blind Revenge, I spent a week in Palm Springs, California, where the novel is set. I ran the exact route my main character ran every morning. In my first draft of the manuscript, I made no mention of the pungent smell of manure that permeated the desert air as I neared the horse stables that bordered the drainage culvert. Nor did I write about the distant hum of vehicle traffic from the main thoroughfare. Some things Google just can’t capture.

Technical Material

While doing scientific research for a particular thriller, I am not only delving into one specific topic but am also constantly on the lookout for the next technological advancement that will appear in the book. So my research efforts are ongoing. I read a lot of nonfiction, most technical in nature, subscribe to several science magazines, conduct extensive online searches, interview experts on the technical subject matter I have chosen for a book, and I draw upon personal experience, as I did in Gadgets. While working for CooperVision Surgical, an ophthalmic company, I held the position of product manager for their laser line.

Firearms and Knives

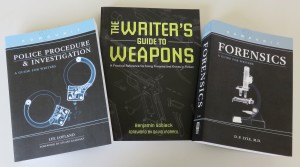

I learned to shoot at a fairly young age and was taught, early on, about the responsibility and safety issues of gun ownership. But writers who aren’t inclined to own a firearm should visit a gun store and ask questions, talk to weapons experts, and interview police officers and/or FBI agents. Many writers’ conferences and writers’ workshops host speakers and panel discussions by various law enforcement agencies. Attend those courses and ask questions. Another resource is The Writer’s Guide to Weapons, by Benjamin Sobieck.

CSI

In Brainwash, Darcy and Ed Clark, a forensic scientist, investigate a crime scene in an arroyo (a steep-sided gully cut by running water in an arid or semiarid region) on Darcy’s land in Taos. As a starting point, I read Forensics: A Guide for Writers by D.P. Lyle, M.D., as well as Police Procedure & Investigations: A Guide for Writers by Lee Lofland. Both books are part of a Howdunit Series published by Writer’s Digest Books. Another good source was sitting in on panel discussions and listening to qualified speakers at writers’ conventions who gave workshops and talks on CSI work. Fascinated by the topic, I spent months researching anything CSI related, most of the information gleaned from material I found online or from books I had purchased on the subject. Only then was I ready to break down the information that applied to the scenes in Brainwash. As for types of crime scene searches, I researched overlapping zone searches, strip searches, spiral searches, and grid searches. I opted for a grid search as the most thorough technique for hunting for evidence in the arroyo. I did some in-depth reading on lifting shoe prints, dusting for fingerprints, collecting evidence, and how best to protect that evidence from contamination until it could be analyzed by a test laboratory. Because I anticipate that Darcy will be involved in future CSI work, my research is ongoing. Another valuable site has been the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, and last month I read Marilyn T. Miller’s book, Crime Scene Investigation Laboratory Manual. Ms. Miller is a former crime scene investigator and forensic scientist. And lately, I finished digesting the Texas Law Enforcement Explorer Training Guide. In closing, true firsthand knowledge can’t be beat, but acquiring it isn’t always practical, and today via certain social media sites and other online resources, there is a wealth of information at your disposal. All you have to do is seek it out.

In Brainwash, Darcy and Ed Clark, a forensic scientist, investigate a crime scene in an arroyo (a steep-sided gully cut by running water in an arid or semiarid region) on Darcy’s land in Taos. As a starting point, I read Forensics: A Guide for Writers by D.P. Lyle, M.D., as well as Police Procedure & Investigations: A Guide for Writers by Lee Lofland. Both books are part of a Howdunit Series published by Writer’s Digest Books. Another good source was sitting in on panel discussions and listening to qualified speakers at writers’ conventions who gave workshops and talks on CSI work. Fascinated by the topic, I spent months researching anything CSI related, most of the information gleaned from material I found online or from books I had purchased on the subject. Only then was I ready to break down the information that applied to the scenes in Brainwash. As for types of crime scene searches, I researched overlapping zone searches, strip searches, spiral searches, and grid searches. I opted for a grid search as the most thorough technique for hunting for evidence in the arroyo. I did some in-depth reading on lifting shoe prints, dusting for fingerprints, collecting evidence, and how best to protect that evidence from contamination until it could be analyzed by a test laboratory. Because I anticipate that Darcy will be involved in future CSI work, my research is ongoing. Another valuable site has been the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, and last month I read Marilyn T. Miller’s book, Crime Scene Investigation Laboratory Manual. Ms. Miller is a former crime scene investigator and forensic scientist. And lately, I finished digesting the Texas Law Enforcement Explorer Training Guide. In closing, true firsthand knowledge can’t be beat, but acquiring it isn’t always practical, and today via certain social media sites and other online resources, there is a wealth of information at your disposal. All you have to do is seek it out.

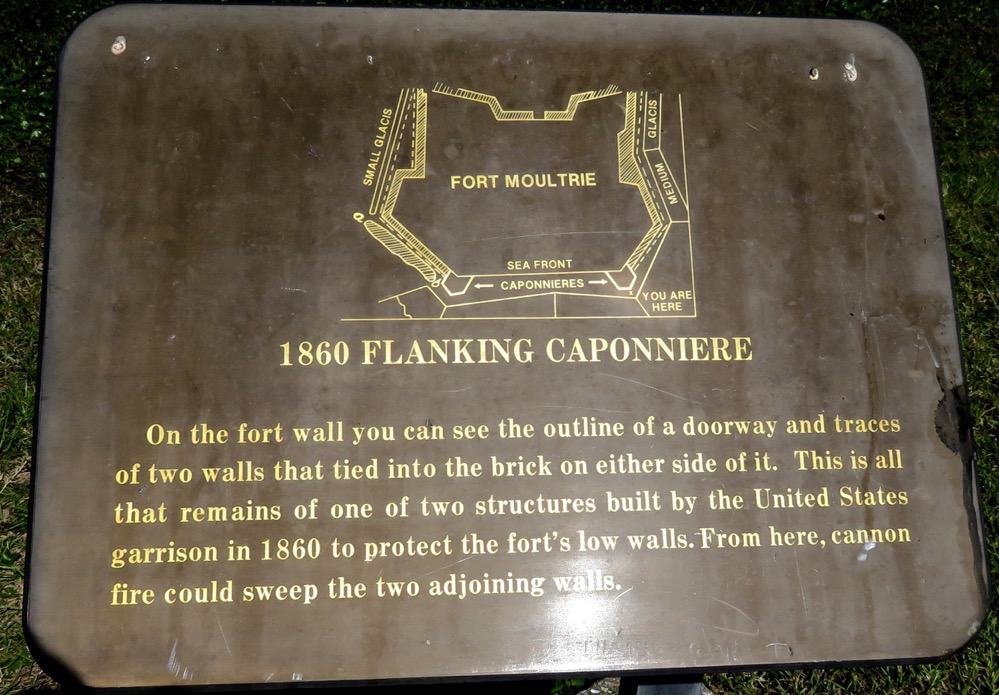

Glossary/Photo Blogs

I plan to devote several blogs to a glossary. I will give a detailed description of each term and include a photo for easy identification. I also plan to do a series of photo blogs showing the exact locations I chose for scenes in my novels, such as the Brainwash crime scene in the arroyo on Darcy’s land in Taos.

Until then, Happy New Year and best wishes for 2016!