In my last post, I blogged about my alma mater, Lincoln Memorial University (LMU) in Harrogate, Tennessee, in the Cumberland Gap, near the junction where Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia meet. Proud of the university’s continued success, high college rankings, and flourishing private school, I satisfied my renewed curiosity in the campus and the history of the region by doing some in-depth research on the school and eastern Tennessee in general. This delving led me to Dr. Earl J. Hess’s book, Lincoln Memorial University and the Shaping of Appalachia. I immediately placed my Amazon order, only to discover that the book is temporarily out of stock. Dr. Hess is a student of Civil War history and grew up in rural Missouri. Since 1989, he has been at LMU and is an associate professor of history. He is also well published. I am eagerly awaiting my copy of his book.

The morning after we visited LMU, a heavy smoky-blue fog hung over the mountains, and mist specked our jackets as we prepared to leave the Inn on Biltmore Estate for the drive from Asheville to Charleston, South Carolina. Although the hotel staff in Charleston had assured us the city hadn’t experienced severe flooding, we decided to leave Asheville early, giving ourselves plenty of time to make the four-hour drive south, especially since Columbia was one of the areas hardest hit by Hurricane Joaquin. As it turned out, we experienced no high-water delays along Highway 26 but did lose an hour stuck in two accidents. One involved several cars—no one badly injured, thank goodness—and the other, unfortunately, was a deer hit by an SUV.

Fountain at Waterfront Park

Charleston is a charming, colorful town, steeped in history. Although I love all things modern and thrive on being a minimalist, I have a fascination for historic buildings—their architecture and their stories. The moment I threw back the curtains in our hotel room at the Belmond Charleston Place, I immediately noticed all the church spires. Other loves of mine are houses of worship and cemeteries, so a church tour was definitely on my agenda. But first Dave wanted to see the waterfront, so we put our church tour on hold until the next day.

Waterfront Park Promenade

We stepped out of our hotel to a humid, subtropical afternoon, but as we neared Waterfront Park a soft breeze coming off the coast squelched any real heat. The park has great views of the Charleston Harbor and the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge, a white, cable-stayed suspension bridge with two diamond-shaped towers that spans the Cooper River. It connects Charleston to Mount Pleasant and is an impressive 573 feet high and 2.7 miles long, and it has eight lanes in addition to a shared twelve-foot-wide pedestrian/bicycle path.

After we strolled Waterfront Park and snapped shots of the water fountains and a sailboat cruising the harbor waters, we took a leisurely walk through the cobblestoned side streets, just soaking in the sunshine and our surroundings, and working up our dinner appetites. That night, we had reservations at McCrady’s Tavern, built in 1778. The restaurant’s entrance is located down a narrow cobblestone alley off East Bay Street. The service was excellent and the food good.

On our first full day in Charleston, we drew straws, figuratively, and agreed to take our island tour in the morning and our house of worship tour in the afternoon. We both wanted to visit Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island. We grabbed coffees to go, hopped into our rental, and sped away toward the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge.

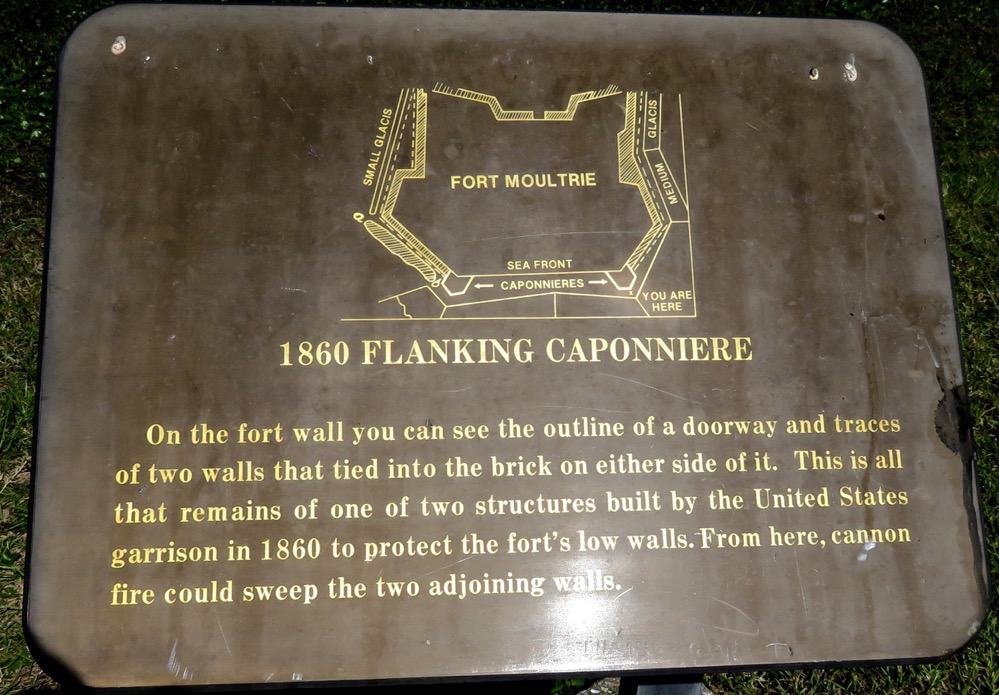

Fort Moultrie, a coastal fortification, was built to guard the harbors and shores of the United States from as early as the first European settlements until the end of World War II. Fort Moultrie has defended Charleston Harbor twice: during the American Revolutionary War when it was attacked by the British fleet, and again nearly a century later during the Civil War when federal forces bombarded Charleston from land and sea. In 1776, after a nine-hour battle when Charleston was saved from British occupation, the fort was named for its commander, William Moultrie.

In early March of 1776, Colonel Moultrie, a former militiaman who was later promoted to general, was ordered to Sullivan’s Island to build a seacoast defense on the shielded harbor. The purpose was to make an invasion as costly as possible, or better still, to prevent invaders from landing. It was unrealistic to think that such a fort, even one well armed with troops and cannons, could annihilate the enemy, but it could certainly slow them down. Any large vessel entering Charleston had to first cross Charleston Bar, a series of submerged sandbanks lying about eight miles from the city. Most ships ran aground and became stuck, and were then more vulnerable to attack.

Work on the square-shaped fort began by cutting thousands of spongy palmetto logs, which became the foundation for an immense pen, five hundred feet long and sixteen feet wide, filled with sand to stop the shot. The workers constructed cannon platforms and nailed them together with spikes. During the construction, George Washington dispatched General Charles Lee and two thousand soldiers to assist in Charleston’s defense. Lee’s appearance alone boosted morale among the South Carolina troops. But after Lee viewed Charleston’s defenses, his worries mounted. Moultrie commanded only thirty-one cannons and a garrison of less than four hundred men. And the fort was hastily erected, with only thick planks guarding the powder magazine, and the curtain walls on the north side of the fort weren’t even finished.

In mid-May, Charlestonians received word that the formidable British fleet was massing at Cape Fear. On June 1, the fleet finally appeared, about fifty sail in all, and anchored outside of the bar. Moultrie termed the battle “one continual blaze and roar,” and it raged on for hours, until the garrison was running out of powder. Word was sent to Lee, and seven hundred pounds of powder reached the fort defenders later in the day, allowing them to fend off the enemy. The British had used thirty-two thousand pounds of powder and the Americans less than five thousand. Within days of the battle came the signing of the Declaration of Independence.

0 Comments