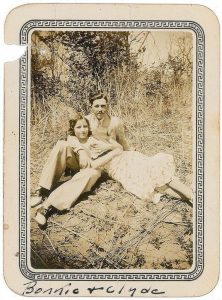

Clyde Champion Barrow and Bonnie Elizabeth Parker met in Texas in 1930. Bonnie was 19 and married to a jailed murderer. Clyde was 21, single, and a free man, but not for long.

Clyde Champion Barrow and Bonnie Elizabeth Parker met in Texas in 1930. Bonnie was 19 and married to a jailed murderer. Clyde was 21, single, and a free man, but not for long.

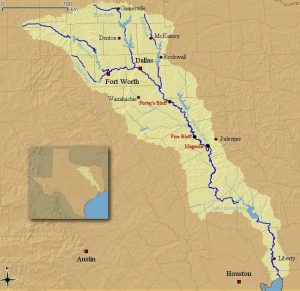

After his arrest for burglary, he went to jail, but escaped with Bonnie’s help. She smuggled a gun to him. He was recaptured and sent back to prison, but paroled in 1932, and the two career criminals returned to their crime spree—murder, armed robbery, and kidnapping—in Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Missouri, to name a few states. The FBI believes they committed at least thirteen murders.

In late 1932, the dangerous duo began traveling with a gunman named William Jones who had replaced a former member—Raymond Hamilton. In 1933, the three joined forces with Clyde’s brother Ivan “Buck” Barrow, recently granted a full pardon by the governor. He and his wife Blanche joined the group. They now numbered five and began making headlines across the country, escaping capture despite various encounters with the law.

But the law prevailed and the hunt for the five intensified. During a shootout in Iowa, Buck was fatally wounded, his wife Blanche captured, and they caught up with Jones in Houston. Bonnie and Clyde escaped unscathed.

Shortly after the death of Buck, and the capture of Blanche and Jones, the Dallas sheriff’s office set up a trap in nearby Grand Prairie, Texas to capture the outlawed duo. But again they escaped the gunfire, carjacked an attorney on the highway, abandoned the vehicle in Oklahoma, and ended up in Shreveport, Louisiana where they committed an armed robbery.

Two months later, in a hail of machine-gun fire, they liberated five prisoners from Eastham State Prison Farm in Waldo, Texas—Raymond Hamilton and a former accomplice of theirs, Henry Methvin.

But the crime that caught my attention happened on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934. State Troopers H.D. Murphy and Edward Wheeler along with State Highway Patrolman Polk Ivy were patrolling Texas 114 in present-day Southlake. Ivy rode north toward Roanoke, but Murphy and Wheeler, seeing what appeared to be a motorist in trouble, turned up Dove Road. Ivy who had ridden several miles up the highway realized his partners had stopped off somewhere and retraced the route to locate them. He found them both lying on Dove Road—dead—pistols still holstered and their murderer(s) gone.

But the crime that caught my attention happened on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934. State Troopers H.D. Murphy and Edward Wheeler along with State Highway Patrolman Polk Ivy were patrolling Texas 114 in present-day Southlake. Ivy rode north toward Roanoke, but Murphy and Wheeler, seeing what appeared to be a motorist in trouble, turned up Dove Road. Ivy who had ridden several miles up the highway realized his partners had stopped off somewhere and retraced the route to locate them. He found them both lying on Dove Road—dead—pistols still holstered and their murderer(s) gone.

A self-proclaimed eyewitness, farmer William Schieffer, claimed that he saw the murders. He contended that Bonnie and Clyde acted alone, murdering the troopers in cold blood. However, upon further questioning, his story changed several times and conflicted with gang member Henry Methvin’s later testimony that he had also participated in the killings.

Weeks after the murders of Murphy and Wheeler, FBI agents learned that Bonnie and Clyde had been seen in the company of Henry Methvin. The elusive duo, along with the Methvins, planned to attend a party at Black Lake, Louisiana and would then return to Texas.

On May 23, 1934 in Sailes, Bienville Parish, Louisiana, one of the most spectacular manhunts in the nation came to a violent end. In the dawn light, a posse concealed in the bushes along the highway, spotted Bonnie and Clyde motoring down the road. When they attempted to speed off, the officers open fired, killing them both instantly.

Side notes: Bonnie and Clyde were known to hang around the area west of Grapevine (now Southlake). When Clyde was a boy, his family lived near what’s now Texas 114 and Kimball, and some of Bonnie’s kin lived on Dove Road.

While I certainly do not condone the actions of Bonnie and Clyde in any way, I do want to point out that there are two sides to every story. The abuse Clyde suffered in prison may have shaped some of his hostilities in life. As for Bonnie, I have no second story, except for a marriage gone bad.

While I certainly do not condone the actions of Bonnie and Clyde in any way, I do want to point out that there are two sides to every story. The abuse Clyde suffered in prison may have shaped some of his hostilities in life. As for Bonnie, I have no second story, except for a marriage gone bad.

Clyde’s side of the story: He, too, did time at Eastham Prison Farm, which Texas Monthly called “the worst of the worst” for the abuse inflicted upon its prisoners. But Clyde also suffered sexual abuse at the hands of an inmate known as Big Ed Crowder. The repeated sexual assaults became unbearable and one night Clyde took matters into his own hands. He beat Crowder to death with a pipe. Another inmate took the rap and Clyde was eventually paroled. A good friend of Clyde’s said prison changed Clyde “from a schoolboy to a rattlesnake.” While in prison, Clyde began formulating his plan for revenge. He’d start a gang, steal money and guns, then return to Eastman to kill all the guards.

In 1996, a 6-foot historical marker commemorating E.B. Wheeler, 26, and H.D. Murphy, 24, was unveiled on Dove Road east of Texas 114. Doris Edwards, the widow of Trooper Wheeler, attended the ceremony. She said she appreciated the memorial because Bonnie and Clyde had become infamous but their victims were often forgotten. “It’s just stayed inside me and festered all this time — all the publicity on Bonnie and Clyde, glamorizing them,” Mrs. Edwards told an Associated Press reporter. “I want the world to know what vicious killers and murderers they are.” (Source: City of Southlake.)

Read more about the nefarious duo: “The Untold Truth of Bonnie and Clyde.”

For a different perspective:“Bonnie and Clyde: 9 Facts About the Outlawed Duo.”