During my research of Texas history, a persistent point kept hitting home –something I had never given much thought to, but should have. Often the accuracy of the details and the authenticity of the events were called into question as contradictions arose in the storytelling. Of the few people who knew the stories, almost none were professional writers. In fact, many pioneers couldn’t read or write and often led solitary lives with no one to witness or chronicle their experiences. Of those who wrote personal journals, their diaries were very late in surfacing, some only in this century. As for the stories handed down by word of mouth, there’s no way to tell if any had been embellished as the narratives passed from one person to the next.

During my research of Texas history, a persistent point kept hitting home –something I had never given much thought to, but should have. Often the accuracy of the details and the authenticity of the events were called into question as contradictions arose in the storytelling. Of the few people who knew the stories, almost none were professional writers. In fact, many pioneers couldn’t read or write and often led solitary lives with no one to witness or chronicle their experiences. Of those who wrote personal journals, their diaries were very late in surfacing, some only in this century. As for the stories handed down by word of mouth, there’s no way to tell if any had been embellished as the narratives passed from one person to the next.

That’s why I read with great interest Journal of A Trapper, a personal log written by frontiersman Osborne Russell, recounting his nine years as a fur trapper in the Rocky Mountains from 1834 to 1843. His firsthand descriptions of the mountain terrain and lush valleys inspired me. As he trapped in the greater Yellowstone region before leaving the solitary mountain life to settle in Oregon, his encounters with grizzlies and wolves were at times hair raising, and his run-ins with the American Indians were sometimes, but not always, hostile.

This rather lengthy prelude brings me to another question. What really happened at the Alamo? When I read historian John Myers’ book on the history of The Alamo, it was obvious that the author had done exhaustive research to lay bare the authenticity of the siege and the legendary characters – Bowie, Travis, Crockett, and Santa Ana – who were behind the heroism that made the Alamo story immortal. But I also wish historians had given more credence to Travis’s slave, Joe, who was interviewed a few days after the siege but whose statements were put aside. He was described as intelligent, and he was there to see what happened – one of the few people able to give a firsthand account. That prompted me to learn more about Joe’s story of the battle at the Alamo. Read more about Joe: https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Joe%20Article.pdf.

My fascination with knowing more about Joe paralleled my prior research on another slave, Bob Jones, who overcame enormous obstacles to become a prosperous landowner in the Roanoke-Southlake area, a well-respected rancher, and family man. Link back to prior blog post on Bob Jones.

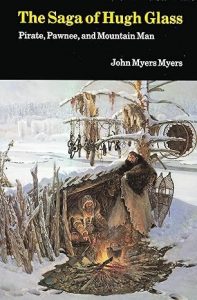

Impressed by Myers’s exhaustive research and his dedication to chronicle the details of the Alamo, I promptly bought his book titled The Saga of Hugh Glass: Pirate, Pawnee, and Mountain Man. Is this legendary hero’s story true? Did Glass survive being mauled by a grizzly bear and, when left for dead by his fellow trappers, have the will and fortitude to crawl for six weeks until he reached the nearest settlement for help? Buy the book and judge for yourself.

Impressed by Myers’s exhaustive research and his dedication to chronicle the details of the Alamo, I promptly bought his book titled The Saga of Hugh Glass: Pirate, Pawnee, and Mountain Man. Is this legendary hero’s story true? Did Glass survive being mauled by a grizzly bear and, when left for dead by his fellow trappers, have the will and fortitude to crawl for six weeks until he reached the nearest settlement for help? Buy the book and judge for yourself.

Then analyze the two movies that were based on Hugh Glass’s life and ask yourself this question. Was either the 1971 movie, Man in the Wilderness starring Richard Harris, or the more recent movie, The Revenant starring Leonardo DiCaprio, an authentic depiction of the remarkable real-life survival story of Hugh Glass? Or were they more Hollywood than historically accurate?

Hitting closer to home, how many of us have taken time from our busy schedules to chronicle our own lives? When was the last time we sat down with our family and asked those all-important questions that seem to arise after our loved ones are deceased? I often find myself thinking, “Why didn’t I ask before they passed on? Now I’ll never know.”

On a side note but related, almost every time I charge my camera batteries I muse, What a great invention! How I wish digital SLRs had been around during all those years of growing up overseas. Sure, I have Polaroids, but the quality is lacking and fades with age. On the other hand, photos in general are wonderful visual memories of times past. I did keep a diary of those informative years aboard, and I’m thankful that my father kept a log . . . of certain events. But nothing compares to a face-to-face talk to get the facts, cutting out the fiction or contradiction from the truth.