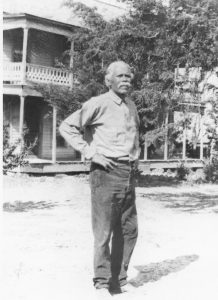

In attendance was Bob Jones’ grandson Dr. William Jones. Photo courtesy of the Southlake Historical Society. Art location: Bob Jones Park, Southlake, Texas. Artist: Seth Vandable.

My first giant schnauzer was named Shotz. One of her favorite pastimes, besides a walk in the park, was to simply go for a ride in her 4Runner. One morning, I loaded her into our SUV and we drove to north Southlake to check out a new park—Bob Jones Park. We walked the trails for over an hour, and then drove down Bob Jones Road to where it came to a dead-end. The land beyond the end of the road had been in the Bob Jones family since 1868—certified by the Family Land Heritage. I left the area wondering: “Who was Bob Jones?”

After reading about Bob Jones, I will say he was someone I wish I had known—a man who overcame the adversities of the time to become a prosperous landowner in the Roanoke-Southlake area and a well-respected rancher and family man.

John Dolford Jones, nicknamed “Bob,” was the son of a white man, Leazer Alvis Jones, who bred racehorses in South Carolina, and his slave Elizabeth. Around 1859 Leazer left his white wife in Arkansas and moved to Texas with Elizabeth and his two sons Bob and Jim. They lived on a farm near Elizabethtown and the Medlin community, present-day Roanoke.

In 1861 Bob Jones was freed near the Medlin community, and herded sheep for a livelihood. He bought his first 60 acres of bottom land from his father and began to farm and raise livestock. His hard work increased his landholdings to 2,000 acres on the Tarrant-Denton county line.

Living alone left a lot to be desired, so he took a friend’s advice and one weekend attended a dance in Bonham. There he met Almeady “Meady” Chisum, also born into slavery. Her father was cattle baron John Simpson Chisum, and his slave Jensie, Meady’s mother. In 1875 Bob and Meady were married and they eventually had ten children.

Like most pioneering families, the Jones family were self-sustaining farmers that planted a vegetable garden and orchard, and raised chickens, hogs, milk cows, and sheep, and planting cotton and corn for the livestock. Bob supplemented his income by raising horses. Many of his deals were made with only a handshake as collateral: debts settled when his “crops came in.”

As many have said, Bob Jones was an exceptional man who worked around life’s obstacles. Both he and his wife Meady valued education. When his children and grandchildren couldn’t attend white schools in a segregated society, that didn’t stop Bob. He’d hire teachers to teach at the church he built—Mount Carmel Baptist Church.

After the school term ended, Bob hired a private teacher to live on his farm to teach his children spelling, history, English, arithmetic, and geography throughout the summer months. At one time he bought a home in Denton, and each spring, Meady and the children moved there so that the children could attend school, but that proved disruptive to farming the land. His solution? Build a one-room school house next to their home in Roanoke, which allowed the children to attend school year round and they could still tend to their farming chores.

In 1920, for the benefit of his children as well as other black children, he donated an acre to the county for “colored” schools and built Walnut Grove School near Bob Jones Park. By the 1940s, when not many of Jones’s grandchildren were still living in the area, several families were invited to the Jones community so that their children could be schooled.

Christmas Day 1936, Bob Jones passed away. Over 500 people, black and white, were in attendance at this funeral. Upon his death, Bob had divided his land among his children. One of the youngest, Eugie, swapped her land with her brother Emory, so she could keep the 40 acres that was the “home place.”

In the mid-1940s, the Army Corps of Engineers began planning Lake Grapevine. Much of the original Jones land, situated along Denton Creek, was taken by eminent domain.

In 1948, the family home burned down, but Eugie and her husband McKinley rebuilt “just up the hill a piece” from the original homesite. Before Meady died in 1949, she told Eugie, “Don’t sell the home place. The children need a place to come home to.”

In early 1950, tragedy struck again with the construction of the Grapevine Reservoir. When the plan changed to include the family home and the 40 acres around it, Eugie fought back. Long court battles ensued, but for two years, Eugie refused to give up her land. Then one day she received a letter saying she could keep the land but had to return the money. She slipped the uncashed checks into an envelope and sent them back to Washington DC.

My father once told me that there are two things in life you can never have enough of—land and trees. So to know that today most of Bob Jones’s land is under water is a sad finality for me.

In 1976, seated on a screened-in porch, gazing at the sailboats on Lake Grapevine, Eugie Jones Thomas recalled her childhood days as one of the ten children of Bob and Almeady Jones.

She stated that Grapevine Reservoir hasn’t bothered her too much. There is a good fishing hole at the end of her road, but she keeps it open so that people can get to the “place where the fish always bite.”

“I have always worked and I have always been happy. I don’t worry or grieve. I have lived a good true life—a Christian and faithful life. You have got to have faith.” This philosophy of life has been the guideline of Eugie Jones Thomas, the granddaughter of John Simpson Chisum, for 90 years.

As many stated, and I agree, Bob Jones was an exceptional person—a heritage of work, education, family pride, self improvement, and a love of the land.

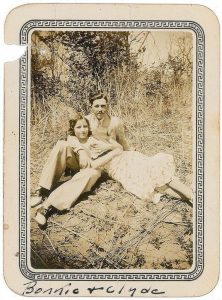

Clyde Champion Barrow and Bonnie Elizabeth Parker met in Texas in 1930. Bonnie was 19 and married to a jailed murderer. Clyde was 21, single, and a free man, but not for long.

Clyde Champion Barrow and Bonnie Elizabeth Parker met in Texas in 1930. Bonnie was 19 and married to a jailed murderer. Clyde was 21, single, and a free man, but not for long. But the crime that caught my attention happened on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934. State Troopers H.D. Murphy and Edward Wheeler along with State Highway Patrolman Polk Ivy were patrolling Texas 114 in present-day Southlake. Ivy rode north toward Roanoke, but Murphy and Wheeler, seeing what appeared to be a motorist in trouble, turned up Dove Road. Ivy who had ridden several miles up the highway realized his partners had stopped off somewhere and retraced the route to locate them. He found them both lying on Dove Road—dead—pistols still holstered and their murderer(s) gone.

But the crime that caught my attention happened on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1934. State Troopers H.D. Murphy and Edward Wheeler along with State Highway Patrolman Polk Ivy were patrolling Texas 114 in present-day Southlake. Ivy rode north toward Roanoke, but Murphy and Wheeler, seeing what appeared to be a motorist in trouble, turned up Dove Road. Ivy who had ridden several miles up the highway realized his partners had stopped off somewhere and retraced the route to locate them. He found them both lying on Dove Road—dead—pistols still holstered and their murderer(s) gone. While I certainly do not condone the actions of Bonnie and Clyde in any way, I do want to point out that there are two sides to every story. The abuse Clyde suffered in prison may have shaped some of his hostilities in life. As for Bonnie, I have no second story, except for a marriage gone bad.

While I certainly do not condone the actions of Bonnie and Clyde in any way, I do want to point out that there are two sides to every story. The abuse Clyde suffered in prison may have shaped some of his hostilities in life. As for Bonnie, I have no second story, except for a marriage gone bad.